Many believe an ancestral journey is simply an emotional experience of “connecting with the past.” The reality is far more profound. This journey is an act of neuro-historical archaeology, where the physical environment, forgotten records, and family myths converge to actively re-wire your identity. It’s not just about finding who you were; it’s about discovering the biological and narrative forces that construct who you are right now.

There is a moment in every genealogist’s quest that feels like a whisper across time. It might be the curve of a signature on a faded document or the unexpected familiarity of a cobblestone street in a town you’ve never visited. This pull towards our origins is a deeply human impulse. Many embark on a “roots trip” expecting a sentimental vacation, a simple tour of ancestral landmarks. They prepare by building family trees and packing cameras, anticipating a pleasant connection to a vague, historical past.

The conventional wisdom is that such a journey provides a “sense of belonging.” But this explanation barely scratches the surface. It fails to capture the almost physical shift that occurs when you stand on the same soil as your great-great-grandparents. What if the key to understanding this transformation isn’t just in the emotions you feel, but in the neurological, historical, and architectural data you process? What if your very definition of “self” is not a fixed point, but a story actively being co-authored by you and the ghosts of your past?

This exploration moves beyond the simple “what” and “where” of genealogical tourism to uncover the profound “why.” We will dissect the dopamine hit of a census record discovery, learn to navigate the conflict between cherished family myths and cold-hard facts, and understand why some ruins feel electrically alive while others are just piles of stone. This is not just a guide to visiting the past; it’s a map to understanding how the past visits you, changing you from the inside out.

To fully grasp this transformative process, this article breaks down the key psychological and practical elements of an ancestral journey. The following sections will guide you through the intricate web of memory, documentation, and place that combine to reshape your personal history.

Summary: Why Visiting Your Ancestral Home Changes Your Definition of “Self”?

- Why Finding a Name on a Census Record Triggers a Dopamine Response?

- How to Access Local Parish Records That Are Not Digitized Online?

- Grandma’s Memory vs. Birth Certificates: Which Source Should You Trust?

- The “Mandela Effect” in Family Stories: How to Verify Tall Tales?

- How to Digitize 100-Year-Old Photos Without Damaging the Originals?

- Autobiography vs. Biography: Which Reveals the Truth About a Public Figure?

- Why You Remember History Better When You Stand Where It Happened?

- Why Some Ruins Feel “Alive” While Others Feel Like Piles of Stone?

Why Finding a Name on a Census Record Triggers a Dopamine Response?

The moment of discovery in genealogy is a potent experience. After hours of scrolling through digitized microfiche, you find it: a familiar surname, an ancestor’s occupation listed as “wheelwright,” a child’s name you only knew from a whispered story. The sudden rush of exhilaration and validation is not just a fleeting emotion; it’s a profound neurological event. This “genealogy high” is the brain’s reward system in action, driven by the neurotransmitter dopamine. It’s the chemical signature of finding something you were seeking, a reward for your patient hunt.

This response is deeply rooted in our brain’s architecture. As researchers have pointed out, the brain doesn’t just release dopamine for predictable pleasures. The real power lies in the unexpected. According to a Nature Neuroscience study on dopamine neuron subtypes, these cells are uniquely tuned to fire in response to surprising rewards. The discovery of an ancestor in a place you didn’t expect, or finding their name spelled in a way that finally solves a family puzzle, is precisely this kind of unexpected prize. It confirms the hunt was worthwhile and motivates you to continue the quest.

This neurological reaction is the engine of genealogical research. It transforms a dry, academic task into a thrilling treasure hunt. Each small find—a date of birth, a shipping manifest, a previously unknown sibling—delivers a small but potent dose of dopamine, reinforcing the search behavior. It’s the brain’s way of saying, “This matters. Keep digging.” As Nature Neuroscience researchers explain:

Dopamine neurons are characterized by their response to unexpected rewards, but they also fire during movement and aversive stimuli.

– Nature Neuroscience researchers, Nature Neuroscience study on dopamine neuron subtypes

This chemical reward is the starting point of the identity shift. It validates that these long-gone people are not just names, but real, findable individuals to whom you are connected. The abstract concept of “heritage” becomes a concrete, verifiable reality, one dopamine hit at a time.

How to Access Local Parish Records That Are Not Digitized Online?

While online databases have revolutionized genealogy, the deepest secrets often lie offline, in the quiet, dusty archives of local parishes. These records—baptismal fonts, marriage registers, burial logs—are the lifeblood of pre-20th-century research. They contain the intimate details of life that were never meant for digital consumption. Accessing them requires a different kind of archaeology, one that involves patience, preparation, and respect for the keepers of these fragile histories.

The first challenge is that these are not public libraries. Many are still active churches or small municipal offices with limited staff and no formal process for genealogical inquiries. Success depends on treating the process not as a demand for information but as a respectful request for assistance. You are a guest delving into a community’s preserved memory. A polite email or phone call, clearly stating your ancestral connection and what you hope to find, is the essential first step. This is where you move from a data-miner to a historical ambassador for your family.

Once you secure a potential appointment, preparation is everything. Unlike a searchable database, you cannot simply type in a name. You must arrive with specific date ranges, names, and potential alternate spellings. The time you are granted may be short, and the archivist’s patience is a finite resource. Being prepared shows respect for their time and maximizes your chances of a breakthrough.

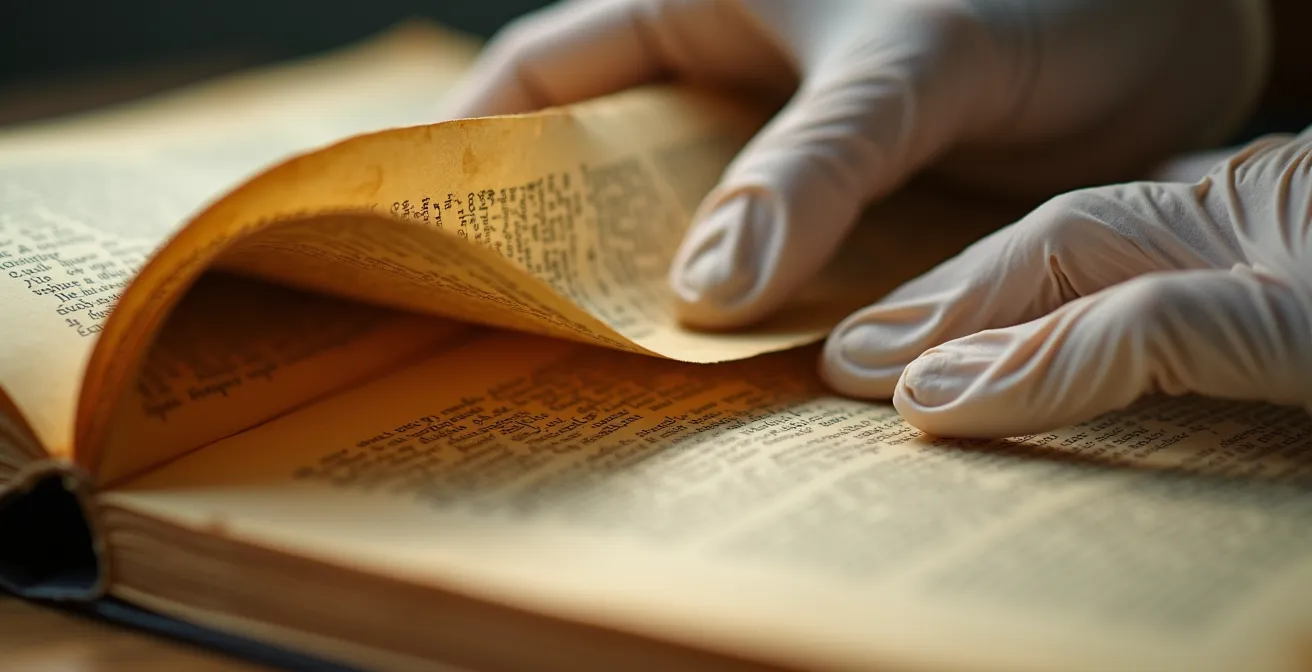

Handling these documents is a physical connection to the past. The texture of the century-old paper and the faded ink are a tactile reminder of the person who made that mark. This direct contact with primary sources is irreplaceable. To ensure you can conduct this research effectively and respectfully, a clear plan is necessary.

Your Action Plan: Accessing Undigitized Parish Records

- Initial Contact: Contact the parish office directly via phone or email to inquire about archive access policies, visiting hours, and any potential fees for research or copies.

- Prove Your Purpose: Prepare documentation proving your genealogical research purpose and direct family connection to the individuals you are researching. A short, written summary of your family line can be helpful.

- Secure an Appointment: Schedule an appointment well in advance. Many parishes have extremely limited archive access hours, sometimes only a few hours per week, often managed by volunteers.

- Bring Proper Equipment: Arrive with the right tools for handling fragile documents: soft cotton gloves, a pencil and notebook for notes (pens are often forbidden), and a high-resolution digital camera or phone (first, confirm if photography is permitted).

- Maximize Your Time: Arrive with a prioritized list of specific dates and names to research. Your time is precious, so focus on your most critical questions first to ensure you don’t leave empty-handed.

Grandma’s Memory vs. Birth Certificates: Which Source Should You Trust?

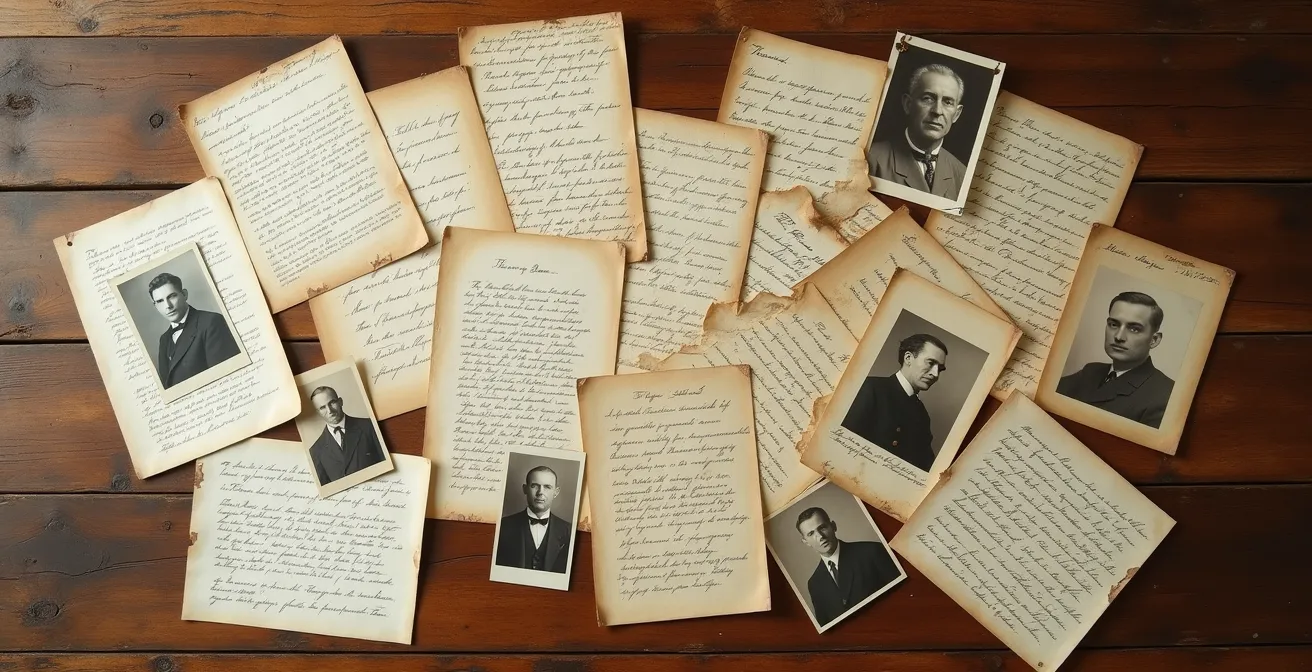

Every family has its canon of stories. There’s the tale of the great-grandfather who was a stowaway, the grandmother who was secretly descended from royalty, or the vaguely remembered name of a “lost” sibling. These oral histories are the emotional fabric of a family, rich with meaning, context, and a sense of identity. But when you place them alongside a stark, official document—a birth certificate with a different date, a census record with an unknown name—a conflict arises. Which source holds the “truth”?

The mistake is to assume one must be right and the other wrong. A birth certificate provides a fact: a name, a date, a place. It is a snapshot of a legal moment. Your grandmother’s memory, however, provides the narrative. It contains the “why” behind the “what”—the emotions, the social pressures, the family dynamics that a legal document can never capture. For example, a birth certificate might list a child’s birthdate in March, but family lore insists the baby was born in January. Further research might reveal the parents were unmarried, and delaying the registration was a way to obscure the timing of the birth, a crucial piece of the family’s social history.

The most profound understanding of an ancestor comes not from choosing one source over the other, but from using both to build a more complete picture. This method, known as narrative triangulation, is a cornerstone of advanced genealogical research. As the experts at AncestryProGenealogists explain, the real truth is found in the synthesis:

The ‘real truth’ lies in the triangulation between three sources: the autobiography (self-perception), the biography (external perception), and primary source documents from the time.

– Ancestry research methodology, AncestryProGenealogists heritage research guide

This approach reframes the question. Instead of asking “Which is true?”, we should ask “Why does this discrepancy exist?”. The gap between the official record and the family story is often where the most interesting human drama lies. Trust the birth certificate for the fact, but trust your grandmother’s memory for the meaning. The tension between the two is where your ancestor’s story truly comes to life.

The “Mandela Effect” in Family Stories: How to Verify Tall Tales?

The “Mandela Effect” describes a phenomenon where a large group of people shares a false memory of a past event. In genealogy, this is a constant companion. Entire family branches might “remember” an ancestor arriving from Ireland during the famine, only for DNA tests and shipping records to prove they actually came from Scotland a century earlier. These are not lies; they are collective myths, stories that have been told so many times they’ve replaced the original facts to serve a specific narrative purpose—creating a more dramatic or cohesive family identity.

Verifying these “tall tales” requires a multi-pronged approach, treating family lore as a hypothesis to be tested rather than an infallible truth. Oral history is a starting point, providing clues and emotional context, but it is rarely a reliable source for hard facts like dates and locations. The most powerful tool for cutting through generations of myth is often genetic genealogy. DNA doesn’t care about a good story; it reports on biological reality.

Case Study: Genetic Testing Reveals Family Myth Patterns

The power of DNA to dismantle long-held family myths is well-documented. A study involving 30 million DNA test participants revealed common patterns where perceived ethnic heritage differed dramatically from genetic reality. For instance, many American families with a strong “Native American princess” narrative discovered no such ancestry in their DNA. The research found that these stories often served a social function: to create a more compelling or foundational identity narrative for the family in a new land, rather than to preserve factual accuracy. The initial shock reported by participants was often followed by a period of identity reconstruction, as they reconciled their lifelong story with new biological evidence.

This doesn’t mean all family stories are false, but it does mean every element must be cross-referenced with more reliable sources. A multi-layered verification strategy is essential, weighing each type of evidence according to its strengths.

This table, based on common genealogical practices highlighted by organizations like FamilySearch, illustrates how to weigh different sources of information.

| Verification Method | Reliability Score | Best Used For |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Testing | 95% for ethnicity | Biological relationships, ethnic origins |

| Official Records | 90% for facts | Dates, locations, legal names |

| Oral History | 60% for details | Family dynamics, emotions, context |

| Physical Evidence | 85% when authenticated | Photos, letters, artifacts |

Ultimately, verifying tall tales isn’t about proving Grandma wrong. It’s about being a better historian of your own family, understanding that stories are created for meaning, while records are created for fact. The true, rich history of your family lies at the intersection of both.

How to Digitize 100-Year-Old Photos Without Damaging the Originals?

The old shoebox filled with sepia-toned photographs is a genealogical treasure chest. These images are often the only visual link to ancestors, capturing a glance, a posture, or a moment in time. But these artifacts are incredibly fragile. They are susceptible to light, humidity, and the oils from our hands. The act of preserving them through digitization is a critical, but delicate, process. Doing it incorrectly can cause more damage than a century of benign neglect.

The primary enemy of old photographs is physical stress. Automatic document feeders on all-in-one printers are a death sentence for brittle, century-old paper. They can bend, crack, and tear irreplaceable images. The only safe method is a high-resolution flatbed scanner, which allows the photo to lie flat without any mechanical feeding. Even then, care must be taken. If a photograph has a natural curve from age, it should never be forced flat against the glass. This can crack the emulsion layer where the image resides. Instead, gentle pressure from a clean, soft microfiber cloth over the back is sufficient.

Your workspace is as important as your equipment. A clean, dust-free environment prevents particles from getting trapped between the photo and the scanner glass, which can create permanent marks on your digital copy or even scratch the original. The process should be methodical and documented, turning the act of scanning into an archival project. Here is a professional protocol for safe and effective digitization:

- Create a Safe Workspace: Work on a clean, flat surface in an area with controlled humidity (ideally 45-55%) and a stable temperature (65-70°F / 18-21°C). Wear cotton or nitrile gloves to prevent oils from your fingers from damaging the photos.

- Use a Flatbed Scanner: A flatbed scanner is non-negotiable. Set the scanning resolution to at least 600 DPI (dots per inch) to capture sufficient detail for printing and zooming. For very small photos, consider 1200 DPI.

- Handle with Care: Place photos one by one, face-down on the scanner glass. Use a soft, lint-free cloth to gently press the photo flat if needed. Never use tape or adhesives.

- Choose the Right Format: Scan and save the master file in a lossless format like TIFF (.tif). This format preserves all the original data and is best for archival purposes. You can then create smaller JPEG (.jpg) copies from the TIFF file for easy sharing via email or social media.

- Document Everything: As you scan each image, immediately document its metadata. Create a file naming system that includes the date, location, and people identified. In a separate document, write down any family stories or notes associated with each photo. A photo without its story is just an image; with its story, it’s a piece of history.

By following this protocol, you are not just making a copy. You are creating a permanent digital surrogate, ensuring that the faces of your ancestors can be shared and studied for generations to come, long after the original, fragile paper has faded.

Autobiography vs. Biography: Which Reveals the Truth About a Public Figure?

When trying to understand a person’s life—whether it’s a famous public figure or a more private ancestor—we often turn to two primary sources: autobiography (the story they tell about themselves) and biography (the story others tell about them). The common assumption is that one must be more “truthful” than the other. But this framework misses the point. Neither is a pure vessel of truth; both are performances of identity, shaped by memory, motive, and perspective.

An autobiography is an exercise in legacy-building. It is, by its very nature, a curated legacy. The author chooses what to include, what to omit, and how to frame events to present a specific version of themselves to the world. It is invaluable for understanding a person’s self-perception, their motivations, and the values they wished to be remembered by. However, it is an unreliable narrator of objective fact. As one analysis puts it:

An autobiography is not a report; it’s a performance of self, a curated legacy.

– Literary analysis perspective, Narrative Identity Studies

A biography, on the other hand, offers an external perspective. A good biographer acts as a historical detective, assembling facts from letters, interviews, and public records to build a more objective account. It can correct the self-serving narratives of an autobiography and reveal events the subject preferred to forget. Yet, it too is a construction. The biographer brings their own biases, interpretations, and narrative choices to the project, emphasizing certain themes while downplaying others. They were not there; they are reconstructing a life from its traces.

The most complete “truth” about a person is not found by choosing one form over the other. It emerges from the dialogue between them. Where does the autobiography’s account diverge from the biographer’s? What events do they both agree upon, and which are contested? The real person exists in the gaps and overlaps between their own curated story and the story constructed from external evidence. This is the same principle of narrative triangulation we apply to family history: the truth isn’t in a single document, but in the synthesis of all available evidence.

Why You Remember History Better When You Stand Where It Happened?

You can read a hundred books about a historic battle, but you will understand it on a fundamentally deeper level the moment you stand on the battlefield itself. This is the principle of embodied cognition: the idea that our minds are not disconnected from our physical bodies and the environment. When you visit an ancestral home or a historical site, you are not just a passive observer; your brain is actively mapping the history onto a physical space, creating a much stickier and more meaningful memory.

This phenomenon has a clear neurological basis. Recent neuroscience has shown that our spatial memory system is deeply intertwined with our brain’s reward and motivation pathways. A 2024 study demonstrated that spatial memories activate dopaminergic pathways, creating what are known as “goal-location memory” modules in the brain. When you physically stand in a place you’ve only read about, you are giving your brain a powerful geographical anchor for abstract historical facts. The story of your ancestor’s life is no longer just a timeline of dates; it’s a series of events that happened *right here*, in this physical space. This process of neuro-historical resonance transforms abstract knowledge into lived experience.

Case Study: The Biological Familiarity of Heritage Travel

This connection between place and identity may be even deeper than memory, potentially rooted in our DNA. As research into haplogroups (genetic populations with a common ancestor) shows, our DNA carries markers from the geographical locations where our ancestors lived for generations. Travelers on “heritage trips” frequently report an uncanny feeling of familiarity or “coming home” to places they’ve never been. As one traveler to their ancestral homeland in Norway described, there was a “strangely familiar and comforting” sensation in the landscape, a feeling that a deep biological connection to the place was being awakened. This concept of “genetic geography” suggests that the resonance we feel is not just psychological, but biological.

When you walk through the doorway of an ancestral cottage or trace a name on a local war memorial, you are engaging multiple senses. You feel the chill in the air, smell the damp stone, see the way the light falls across the floor. Your brain fuses these sensory inputs with the historical narrative, creating a rich, multi-layered memory that a book or a website could never replicate. History ceases to be a story you were told and becomes a space you have inhabited.

Key Takeaways

- True genealogical insight comes from narrative triangulation: synthesizing official records, oral histories, and physical evidence, rather than trusting one over another.

- The exhilarating “aha!” moment of a genealogical discovery is a real neurological event—a dopamine response to an unexpected reward that fuels the research quest.

- Visiting an ancestral site is an act of embodied cognition; being physically present in a historical space creates far deeper and more lasting memories than simply reading about it.

Why Some Ruins Feel “Alive” While Others Feel Like Piles of Stone?

Not all historical sites are created equal in their power to move us. You can stand before one set of ancient ruins and feel nothing but a mild historical interest. Yet, before another, you can be overcome with a profound sense of connection, as if the ghosts of the past are still present. This difference is not arbitrary; it is rooted in a concept from architectural psychology known as “human affordance.” A ruin feels “alive” when it still affords, or suggests, its original human use.

A pile of rubble is just a pile of rubble. But a ruined wall with a recognizable doorway, a worn stone threshold, and a window frame that still catches the afternoon light feels entirely different. Your brain instinctively recognizes these shapes: a place to enter, a place to look out, a boundary between inside and out. You can imagine someone walking through that door or leaning on that sill. This human scale allows you to mentally project yourself and the lives of others onto the space. The ruin becomes a stage, and your mind begins to populate it with the actors who once lived there.

Architectural Psychology and Narrative Context

A study of heritage sites confirms this principle. Ruins that maintain clear signs of human affordance—like the intact rooms of Pompeii or the tiered seating of the Roman Colosseum—trigger far stronger emotional and imaginative responses in visitors. Crucially, this effect is magnified by narrative. The Colosseum feels alive not just because of its scale, but because we are all steeped in the stories of the gladiators and emperors associated with it. An anonymous, equally old ruin without an attached story or clear human-scale elements often feels inert and silent, because our minds have no narrative framework or architectural clues to bring it to life.

This is the final piece of the identity puzzle. When you visit your ancestral home, you are bringing the most powerful narrative of all: your own family’s story. The crumbling stone wall of a cottage isn’t an anonymous ruin; it’s the wall your great-grandfather built. The worn step is where your grandmother sat. The attached narrative electrifies the space. This combination of human affordance and personal story is what creates the ultimate feeling of connection. It’s the moment the past ceases to be a foreign country and becomes, in a very real sense, your home.

Beginning your own ancestral journey is the first step toward this profound redefinition of self. Start by mapping what you already know, talk to the elders in your family, and identify the first thread of a story you want to verify. The path from a name on a page to standing on the soil of your ancestors is a journey of a thousand small, rewarding discoveries.